Get Ready to Explore

Engage your observations with some reflections by the artist on selected works from the Gallery.

We are excited to bring you a new platform that will help you explore another dimension of some of the images in the Galleries. These are not necessarily what the painting is about, but more like an opportunity for you to overhear a conversation the artist has with his/her own work. The hope is that what you overhear in the conversations might get you thinking more about what you see or get from the painting ... maybe something outside the box.

[Check back with us regularly. What's here is a work in process. Thanks.]

ABOUT WHAT FOLLOWS...

Three things to know about the comments:

1. they are what I had in mind before I started painting;

2. they are what developed during the process of executing the work;

3. or they are what I learned from the painting once it was done.

What I offer does NOT explain the painting or its "meaning." Nor is it what you are supposed to think.

Commentary can be a portal or a curtain. It can open a door for discovery or it can blind you from seeing for yourself. Here it is simply a view from the artist's perspective. As a viewer, you are the one who finishes the painting with your own insights.

.

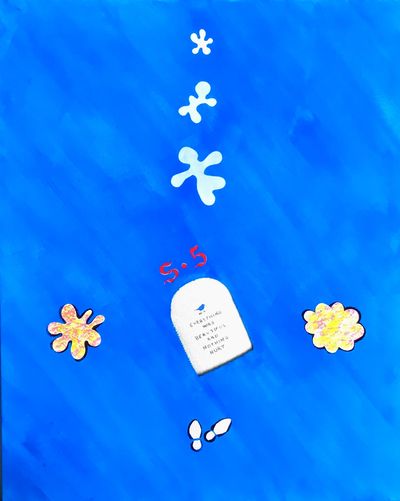

So It Goes

“So it goes,” in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, is what the Tralfamadorians say about the moment one becomes unstuck in time, that is, death. Death is but one of the many moments in life framed from birth by time. Tralfamadorians know that time is non linear, so each of life’s moments is eternal — eternally now, whole, complete, and inextricably bound with every other moment experienced. So, using Tralfamadorian wisdom, no matter how dead one may sometimes seem to be, the focus, the emphasis, instead is on any & every moment that is nice. Recognize it. Call it so. It is forever. What’s nice is beautiful, not hurtful. Be there.

This is what Billy Pilgrim, the anti-hero of Slaughterhouse Five, has learned and what he wants the world to know. Vonnegut characterizes him as a Cinderella. Cinderella is stuck in time knowing that her dream of a beautiful world, however real, is bound by the clock. Billy, unstuck in time knows its conventions and ignores them. This means that he is often looking and behaving like a clown as he endeavors to free from time its deeper truths.

This painting employs the colors, applied sparingly in Vonnegut’s darkly humorous novel. Are they to convey cynicism? or hope? In contrast with the grim and gray ravages of war and destruction, Billy is a sacred fool. Adorned with an azure cape, a fur collar, and shod with silver boots, the smell of life is mustard gas and roses in forms on either side of the entrance to the slaughterhouse. On the door are the words Vonnegut says "would make a good epitaph for Billy--and for me, too." Above the door are human forms of smoke.

Does Billy's cape of blue wrap him with the vastness of sky or space tormented by the savages of war? or does it awaken peace, tranquility and knowledge as yet unrealized? And then there are those silver boots…plodding through the mud and muck of war never losing their luster. They never betray the life they bear. At the end, amidst the senseless insanity and quiet after the fire bombing, Billy dozes in a horse drawn wagon warmed by the sun, awaking to a bird tee-tweeting about it all: the scenery of human folly…and truth. Poo-tee-weet?

Nine of Hearts

At the center of the tree form are nine hearts.

In cartomancy the nine of hearts is the card of joy, satisfaction, and fulfillment in life often associated with love and one’s relational connections both immediate and writ large. In numerology, a “Life Path 9” individual is considered compassionate, creative and disciplined, driven by high ideals with a thirst for knowledge and experience. They are known for their empathy, charisma, and spiritual depth but are challenged by their emotional sensitivity, self-sacrifice, and at times the need to let go.

This is pretty intriguing, but I was thinking of none of it doing this painting. So is it there? I know nothing about either cartomancy or numerology or for that matter any of the esoteric arts. The only thing esoteric here is the artwork. To be both frank and accurate, I learn from my painting. I have often said that for me, art is part of my spiritual practice. There is no hidden meaning that a viewer is supposed to puzzle out and “get.” Above all things, this painting is an illustration of nothing other than what it is in the eye of the beholder.

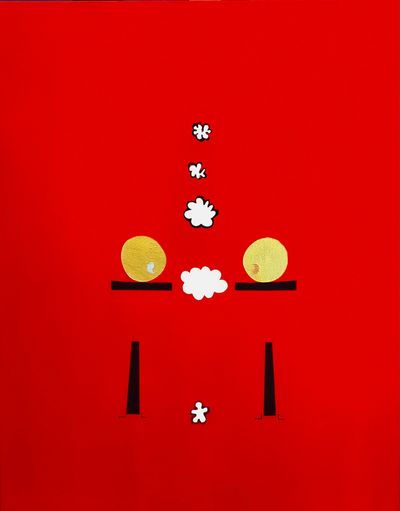

Passage

How does the sacred enter life? Is it an awareness or a wakening of a particular depth of meaning? Is it derived from experience? or is it something that is imposed by culture through convention or learning? In other words, does it arise from within or enter from without?

In Shinto, the indigenous religion of Japan, an architectural structure called a torii is an entrance to a Shinto shrine. It marks a place where kami pass through and are welcomed. The torii is thus a liminal structure through which one moves from the mundane, the everyday presence of ordinary life, into a spiritual realm.

However the torii is not simply the doorway to a temple dividing the sacred from the profane. Torii are erected almost anywhere from a bustling business district to a remote natural vista. Passing through a torii or simply gazing through it like a window what one sees on one side is no different from what one sees on the other. And yet. . . the torii is a gateway. For what? For something we cannot understand and often fail to recognize.